The Barrenlands

A team of Dene researchers are using Indigenous knowledge and Western science to study – and save – the Bathurst caribou herd in Northern Canada

Joe Lazare-Zoe, a Tłı̨chǫ elder from the small community of Gamètì, Northwest Territories, remembers a time when caribou herds were so large that they shook the ground and sounded like thunder.

Joe, an experienced hunter, did not have to go far to provide for his family. The herd was plentiful.

In the 1980’s, the Bathurst caribou herd had a population of nearly half a million animals. And then something changed. The herd began to dwindle.

Today, less than 4,000 Bathurst caribou roam the tundra, and that number continues to fall. The Bathurst caribou are now a species at risk and designated as “critically low”. An entire generation of Indigenous children are growing up without any connection to the animals their ancestors have coexisted with for thousands of years.

Joe Lazare-Zoe shows how hunters would use rock piles as blinds to harvest caribou at water crossings from one point of land to another.

A herd of caribou on top of an esker at the northern end of Contwoyto Lake (Kokètì), Northwest Territories.

A young caribou on the tundra near the Kokètì camp, Northwest Territories.

Noel Football looks out over the barrenlands to watch for predators - wolves and grizzly bears.

Caribou carcasses are left by hunters on the side of the winter road at MacKay Lake, Northwest Territories.

Tracks from a caribou in the beach near a water crossing.

Scientists are stumped by the astonishing population decline of caribou in Canada’s Northwest Territories. Some say the creation of diamond mines have disrupted their migration patterns and calving grounds. Others blame over-hunting.

Researchers point out that climate change has impacted their food sources, while some other experts say the rise in the population of predators, like wolves and grizzly bears, is the cause. Some wildlife observers believe it may be a combination of all of these factors.

Hunting Bathurst caribou has been banned since 2015, but the nearby Beverly herd can be legally harvested. The hope is that the ban will help the Bathurst rebound.

It hasn’t.

Overhunting and poaching of Bathurst caribou is a big concern for governments and conservationists but an even greater concern is the increased hunting of the female cows – pregnant or not, legally harvested or not – that experts say is driving the populations of several herds down. Here, a caribou fetus lays in the snow, evidence that harvesters killed a pregnant cow.

Lloyd Rabesca scouts the landscape in search of caribou at Lac de Sauvage, near the Ekati diamond mine.

A herd of caribou move through the winter landscape at Lac de Sauvage, Northwest Territories.

A flag of an Indigenous man over a maple leaf and covered in caribou blood, is placed along the winter road at MacKay Lake – a sign to passing truckers headed to the nearby diamond mines that hunters are in the area.

In 2016, a group of Indigenous researchers started a program to study the herd, identify why their numbers are so low and find ways to save the caribou from extinction.

The program, called Ekwǫ̀ Nàxoèhdee K’è: Boots on the Ground, uses a mix of traditional Indigenous tracking techniques and Western research methods to study the herd and collect information about the caribou, their habitat, predators and industrial disturbances. Ekwǫ̀ Nàxoèhdee K’è is one of the few Indigenous-led research programs studying caribou in the world.

An aerial view of the Ekwǫ̀ Nàxoèhdee K’è Kokètì camp at Fry Inlet on Contwoyto Lake, Northwest Territories. Research teams work two to three week rotations from late July to late September each year.

Plants, mushrooms and lichen are part of a barren-ground caribou’s diet.

Bobby Nitsiza guts a lake trout at camp.

Nive Sridharan and Stevenson Whane watch a bull caribou walk past them.

Tyanna Steinwand, a manager of research with the Tłı̨chǫ government and a former caribou monitor, says that the camps are a way for Tłı̨chǫ people to reconnect with the land and the wildlife, a key aspect of their life that has been lost due to colonization and hunting restrictions.

“Since we can’t hunt the caribou anymore, the monitoring is a way to get back on the land and to spend time on the land,” she says. “

“I think that’s important, especially for some people who have addictions , when they stay in town and they try – they use our camp like a wellness, a sobering camp even though that’s not really the intended purpose. But, yeah, so I just think having more monitoring and culture camps is a way to get back on the land to heal people.”

Therese Zoe picks wild blueberries near the Koketi camp.

Malcolm Jaeb cuts a caribou leg at MacKay Lake lodge, Northwest Territories.

Stevenson Whane, youth program participant.

Clark Wynter Rabesca

Bailee Nitsiza

The flag of the Tłı̨chǫ nation flies at Koketi camp in 2021.

An evening swim after a long day monitoring caribou on the barrenlands.

Janelle Nitsiza, the Youth Program coordinator for Ekwǫ̀ Nàxoèhdee K’è, braids Hailey Gargan’s hair at the camp kitchen shelter.

Stevenson Whane holds a rosary in his hands. The research teams pray each morning, asking the Creator for safety and guidance for the day ahead.

The monitoring program is unique in its design. Ekwǫ̀ Nàxoède K’è comes from the Tłı̨chǫ language and refers to the movement of the caribou herd throughout the year, from the calving grounds to the forest and back again. It encompasses the whole life cycle of the caribou.

The program’s methodology follows a specific principle drawn from the very ways of life of traditional caribou harvesters: “do as hunters do.” Researchers attend to the herd and the landscape under a holistic concept of “we watch everything” that comes from Tłı̨chǫ Elders. They wait at na’oke, or water crossings, to track details about caribou and the environment, from predators to changes on the landscape from industrial activities.

A Bathurst caribou bull stand on the tundra near Contwoyto Lake, Northwest Territories.

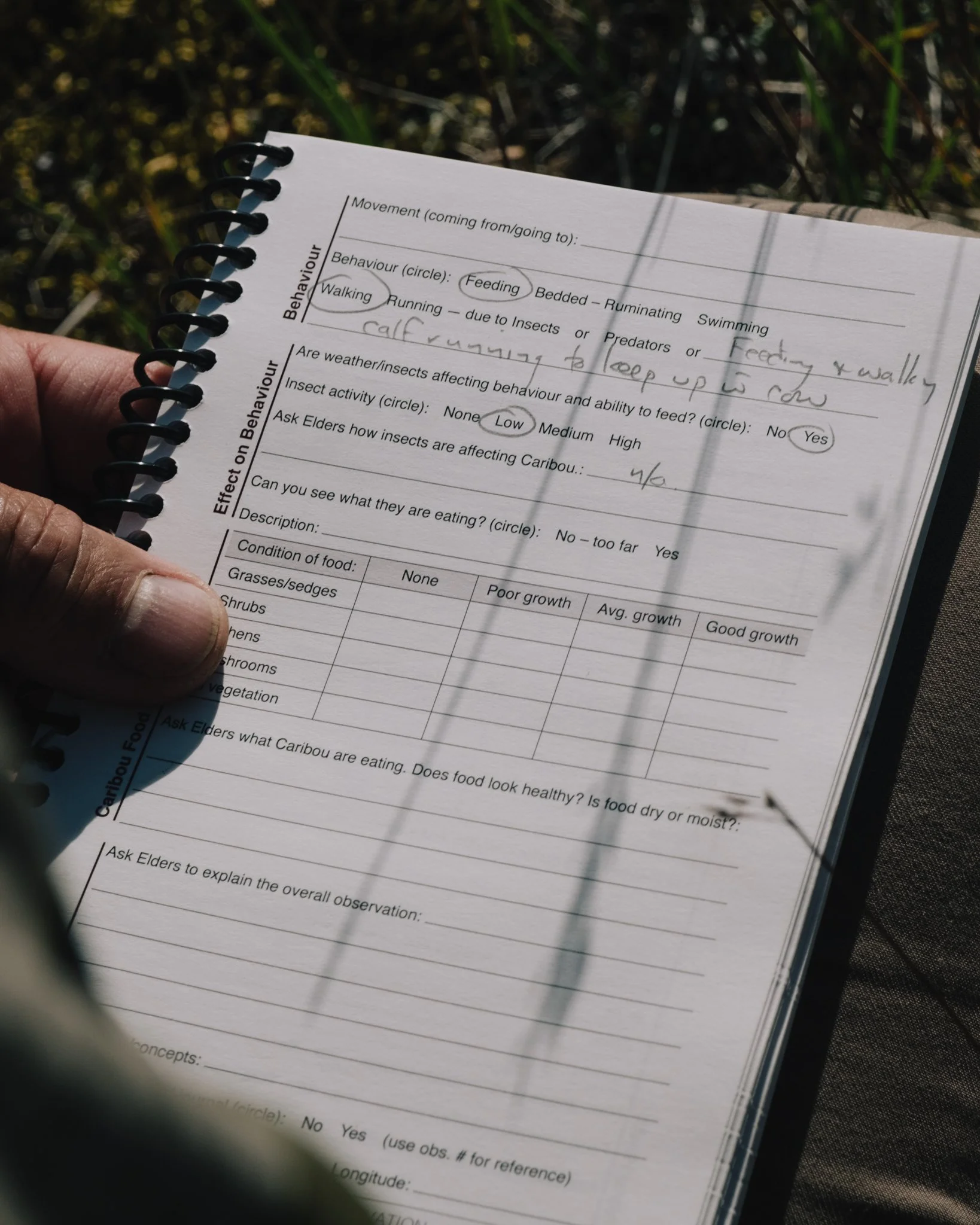

A researcher records caribou sightings and behaviour in their field book.

A guard, keeping watch for grizzlies and wolves, carries a rifle and bag.

The days are long, sometimes monotonous, with several hours of hiking and boating. It is a slow and patient way to study caribou and collect information. But it also allows for rich collaboration. The team — consisting of Tłı̨chǫ Dene Elders, officers from the territory’s Department of Environment and Natural Resources and researchers — make sure everyone is fed, safe from wildlife and rested.

In 2025, youth from across the region were invited to take part in the camps. Most had never been to the barrenlands before, several had never even left their communities. Janelle Nitsiza, the youth program coordinator, says that it is important to have the younger generation be part of the program so they can understand not only how the research works, but also so they can appreciate how important caribou is to them as Dene people.

Shiloh Simpson

Lenon Nitsiza

Reaching back into a rich reservoir of traditional knowledge, these individuals are charting a new way forward when it comes to researching and managing the creatures that share Indigenous lands.

The Ekwǫ̀ Nàxoède K’è: Boots on the Ground program is founded on the belief that local people who rely on the land are in the best position to determine the health of barren-ground caribou.

“The elders have always said that if we respect the caribou and speak positively about them they will return,” says Jocelyn Zoe, one of the program monitors.

“And we need to start speaking about the caribou in a good way. If we use the law of attraction to focus on positive thoughts and words, I believe this can help them become strong again.”