History

Since time immemorial, Indigenous people across the circumpolar world have relied on caribou, and in turn, caribou have relied on people. It is a symbiotic relationship that has spanned generations and borders. Some creation stories say that mankind came from a caribou hoof. Many oral histories are grounded in legends and teachings of living alongside caribou. The animal has been a source of food, clothing, shelter, artwork, music and morals since the first people walked the landscape in what today we call Canada.

Barren-ground caribou are defined in local languages and dialects as tuktu (Inuvialuktun, Inuinnaqtun, Inuktitut), ?ekwȩ (North Slavey), ?etthën (Denesuline) and ekwǫ (Tłı̨chǫ). Caribou are an important part of the sub-arctic ecosystem and a keystone species of cultural value for Indigenous communities.

They are recognized as intelligent and communicative animals. It is through the practice of respect – following traditional laws around behaviour, harvesting, knowledge accumulation and knowledge transfer – that caribou herds remain abundant and healthy and the relationship between caribou and Indigenous people is maintained.

Caribou roam the barrenlands in the Northwest Territories in the 1950’s. Credit: NWTArchives.Busse.N-1979-052-0042

In the late 1800’s, a group of Inuvialuit pose for a photograph with caribou hide sled. Credit: NWTArchives.Gruben.N-2003-038-0073

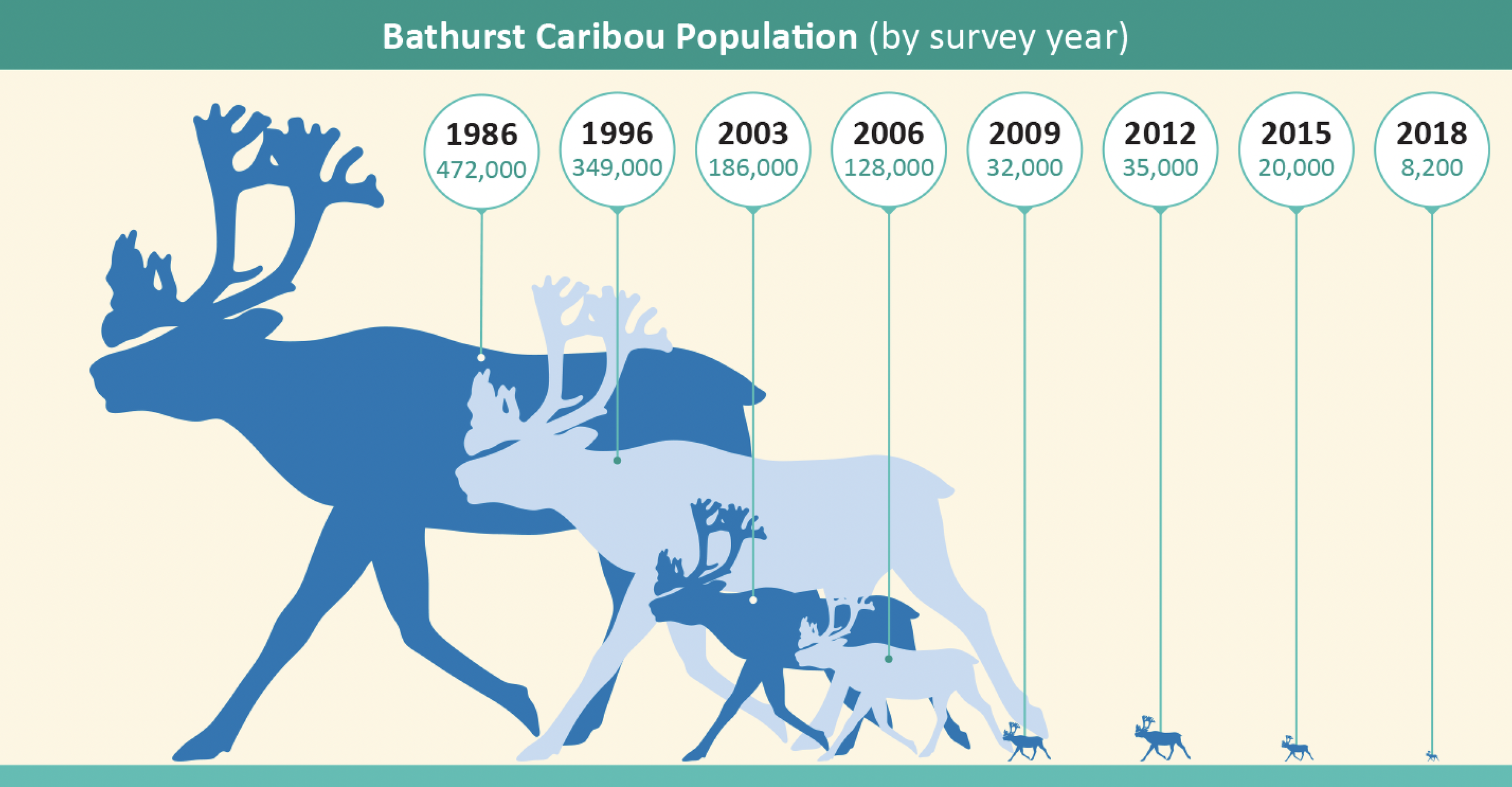

Graphic courtesy The Government of the Northwest Territories

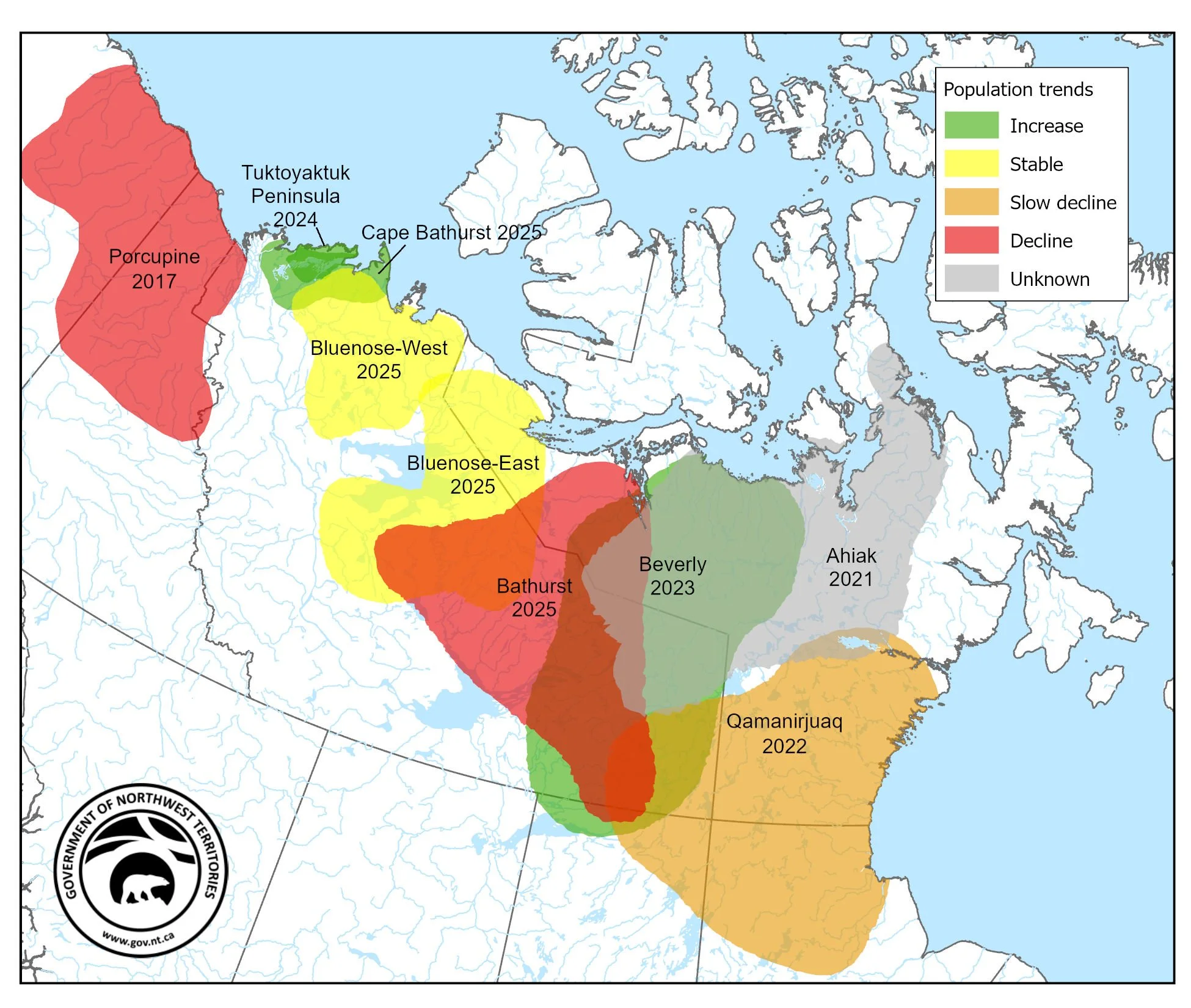

Map courtesy The Government of the Northwest Territories

Children beside a caribou at a home at Little Doctor Lake, Northwest Territories in 1986. Credit: NWTArchives.Kraus.N-1990-022-0046

In Canada, there are three types of caribou: peary, barren-ground and woodland. The Bathurst herd is part of the barren-ground designation and their annual range extends across the Tundra and Taiga biomes of Nunavut and the eastern NWT. In previous years, its winter distribution also reached into the boreal forests of northern Saskatchewan. Scientists know the Bathurst herd as a population of migratory barren-ground caribou that traditionally calves near Bathurst Inlet in the Kitikmeot Region (i.e. central Arctic) of Nunavut. While distinguishing herds by name is typically less important to Indigenous people, they maintain a very detailed understanding of caribou movements across the landscape, key trails and locations that are important culturally for travelling, camping and harvesting or watching overall caribou health and well-being.

Traditional knowledge tells us that caribou use of the landscape has always been dynamic, at times growing larger or smaller, depending on available food, herd numbers, wildfires, winter snow conditions and the influence of caribou leaders on migratory routes. For example, over the past decades, Inuit have watched the Bathurst herd calving ground shift from the east to the west side of Bathurst Inlet.

In the 1980’s the population of the Bathurst caribou numbered at roughly half a million animals. In the following decades, the herd has drastically dropped in numbers. In a 2018 survey, the population was at 8,200 animals.

The 2025 Bathurst herd population estimate is 3,609 adult caribou. This is lower than the 2022 herd estimate of 6,851 adult caribou. This represents a decline of 47% percent over three years. This decline is concerning, given all the efforts of the GNWT and our co-management partners to reduce pressures on this herd through a range of management actions.

In addition to estimates of herd size, the Government of the Northwest Territories’ Department of Environment and Climate Change collects a range of information on key demographic rates, including pregnancy rates and survival rates for calves, cows, and bulls. These factors, along with potential movement of caribou between herds, influence whether a herd is increasing or decreasing. Further work is ongoing to continue to investigate the role of other factors in influencing herd trends for the Bathurst and Bluenose-East herds.

Scientists and researchers are unsure of an exact cause of the population decline but agree that it may be from several factors: climate change, mining activities, overhunting, and a rise in predators.

2025 population estimate:

3,609 Bathurst Caribou

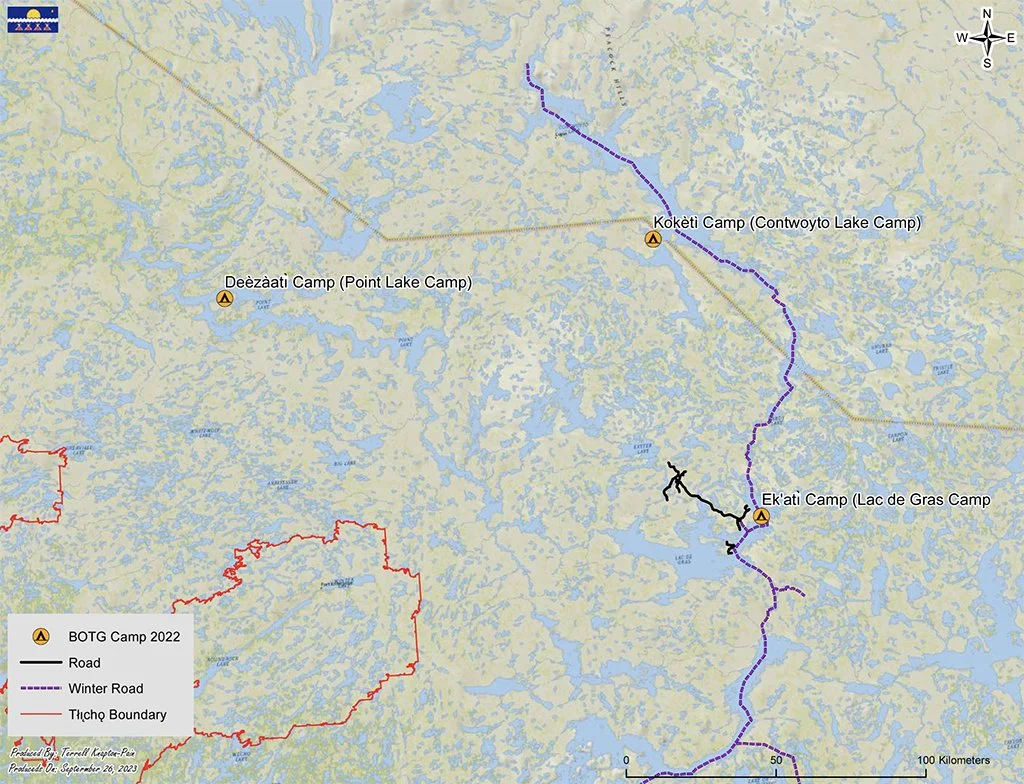

In 2016, the Tlicho government started their own monitoring and research program called Ekwǫ̀ Nàxoèhdee K’è: Boots on the Ground. The program has brought Tłı̨chǫ people to the ancestral harvesting locations on barrenlands. The basecamp at Kokètì (Contwoyto Lake), located in the northernmost region of Tłı̨chǫ traditional territory, is on the summer range of the Bathurst herd; the place where barren-ground caribou migrate with their newborn calves to spend the summer.

In an ongoing commitment, the Tłı̨chǫ Government persistently engages in monitoring programs to study and manage the land and caribou herds, guided by the traditional wisdom of Tłı̨chǫ Elders and harvesters. Both the Bathurst caribou and the Bluenose East herds have undergone significant declines over the past decade. Because of the critical state of the caribou herds and the importance of caribou for the Tłı̨chǫ culture, language and way of life, the Tłı̨chǫ Government continues the program to study and interact with the caribou herds.

The monitoring goal is to assess the state of barren-ground caribou within its summer range, with a specific emphasis on four primary indicators: (1) habitat; (2) caribou health; (3) predator presence; and (4) industrial development impacts. The program is a collaboration between the Tłı̨chǫ Government, GNWT-ECC, the Wek’èezhìı Renewable Resource Board (WRRB). Funding was provided by Tłı̨chǫ Government, Burgundy Diamond Mines Ltd., and the GNWT-Cumulative Impact Monitoring Program1 (CIMP).

Kokètì camp in 2021.

The program operates from three basecamps situated on the barrenlands. The primary basecamp is located at Kokètì, where caribou monitoring efforts have been ongoing for nine years, starting in 2016. In the summer of 2020, an additional base camp was established at Deèzàatì (Point Lake) to monitor the Bluenose East herd. Establishing the caribou monitoring program at Deèzàatì was based on WRRBs (2019) recommendation to expand monitoring to the summer range of the Bluenose East. Deèzàatì was selected because it is the largest waterbody on the Bluenose East range and because of the rich Tłı̨chǫ cultural history on the lake.

In August 2022, the program expanded to Ek'atì (Lac de Gras) and Łıwets’aɂòats’ahtì (Lac du Sauvage). The long-term plan involves establishing a research camp on Łıwets’aɂòats’ahtì, and initiate research and monitoring activities on the lakes around the mines in the years ahead. The research teams were not able to be at Ek'atì during fall 2023, due to wildfire evacuations and severe smoke conditions on the barrenlands making it impossible to land floatplanes at Ek'atì.

Between 2016 and 2024, the monitoring and search efforts of the teams have consistently grown, leading to more frequent and comprehensive wildlife observations. Table 1 provides an overview of the program's annual progression, highlighting the increase in monitors, field days, travel distances, and monitoring hours. Through Ekwǫ̀ Nàxoèhdee K’è, Tłı̨chǫ travel to their ancestral harvesting locations on Kokètì and Deèzàatì, where we reconnect to cultural places and ekwǫ̀. Thus, the program helps Tłı̨chǫ participants to “go back to the original source to remember” (John B. Zoe) the stories, language, knowledge, and cultural ways of life. Through on-the- land monitoring, the ENK program provides an important way for Tłı̨chǫ to continue maintaining the relationship with the land and animals, because “our relationship with ekwǫ̀ defines who we are. It’s a foundation for our nàowo – a Tłı̨chǫ concept that encompasses our language, culture, way of life, as well as our knowledge and laws”.

The teams apply the Tłı̨chǫ research methodology, “We Watch Everything” to study current environmental conditions, cumulative impacts to caribou health and populations, and directly observe caribou in summer and early fall. A second methodology called, “Do as Hunters Do” is formed around traditional ways of traveling the land and sharing knowledge through peoples’ daily activities and interactions on the land. In and around the lakes, the teams travel by boat and on foot to key geographical features known as ekwǫ̀ nǫɂokè (caribou water crossings), where Elders have always anticipated the caribou herds’ arrival. The monitors sit in position, in the same way a traditional hunting party would have done, to wait, and watch the caribou and their habitat. Applying traditional hunting strategies as wildlife monitoring methods, and traditional hunting locations as monitoring places, the teams conduct research by doing what the ancestors did successfully to survive the harsh sub-arctic environment.

To learn more about the Bathurst caribou, and the Ekwǫ̀ Nàxoèhdee K’è program, visit: https://research.tlicho.ca/research/bootsontheground

Map courtesy Tłı̨chǫ Government

Monitoring teams at Kokètì in 2021.

Christine Cleary fleshes caribou hide in Deline, Northwest Territories. Photo by Dorothy Chocolate/NWTArchives.NCS.N-2018-010-12309